Here is the last installment of pre-Columbian settlements in North America, including the first Canadian site, home to the first European settlement.

1003 L’Anse aux Meadows

L’Anse aux Meadows is the only known site of a Norse village in Canada and in North America (outside of Greenland).* It is also the only widely-accepted instance of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. The settlement is notable for possible connections with the attempted colony of Vinland established by Leif Ericson around 1003 and more broadly with Norse exploration of the Americas.

The Norse remains consist of 3 building complexes, each comprising a large dwelling and associated workshops. Finds show evidence of carpentry and ironworking, the first known iron smelting in the New World. Distinctive artifacts include a bronze pin, a spindle whorl, needlework tools and broken wood objects. The presence of the needle and spindle suggests that women were present as well as men.

Not discovered until 1960, the settlement represents the farthest known extent of European exploration and settlement of the New World before the voyages of Christopher Columbus almost 500 years later. It was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1978.

The modern settlement was established as a French fishing station; in 1835 William Decker, an English seaman, founded the present community, which derives most of its income from inshore fishing.

1050 Motul Yucatán

Motul was a site of the Pre-Columbian Maya civilization founded in the 11th century by a priest named Zac Mutul.* After the fall of Yucatán’s central government in Mayapan in the 1440s, the Pech ruled a regional kingdom called Cehpech with its capital in Motul.

With the Spanish conquest of Yucatán, Conquistador Francisco de Montejo made Motul a Spanish colonial town. Motul has a Spanish colonial era Franciscan monastery with interesting frescos.

Motul was granted the status of a city on 22 February 1872.

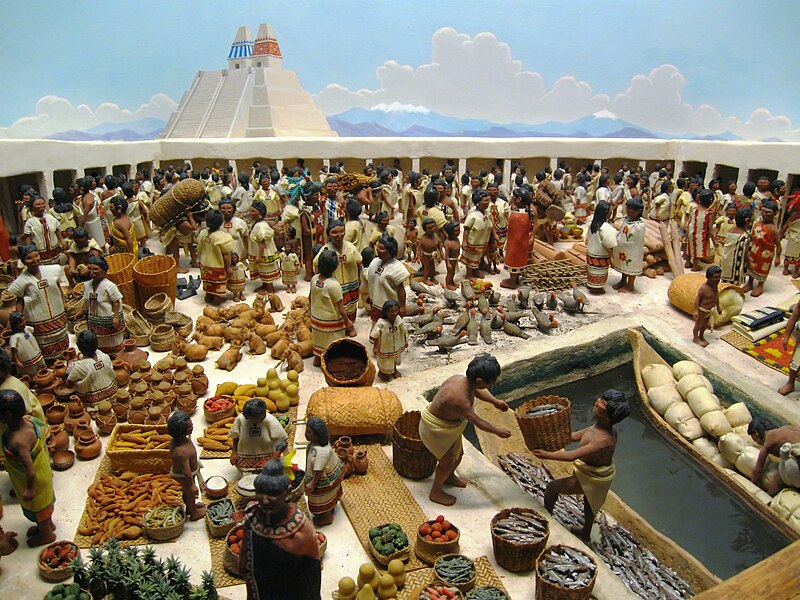

1325 Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan was a Nahua altepetl (city-state) located on an island in Lake Texcoco, in the Valley of Mexico.* Founded in 1325, it became the seat of the Aztec Empire in the 15th century. It was captured by the Spanish in 1521.

At the time of colonization, Tenochtitlan was one of the largest cities in the world; only Paris, Venice and Constantinople were larger. The most common estimates put the population at between 200,000 and 315,000 people.* (pdf)

Its name comes from Nahuatl—tetl=rock and nochtli=prickly pear. It means “Among the prickly pears [growing among] rocks”. Tenochtitlan was one of two Mexican altepetl, the other being Tlatelolco. The city’s site is said to be the fulfillment of an ancient Aztec religious prophecy: that the wandering tribes would find the destined site for a great city whose location would be signaled by an eagle eating a snake while perched atop a cactus. The Aztecs saw this vision on what was then a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco, a vision that is now immortalized in Mexico’s coat of arms and on the Mexican flag.

When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments (…) on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? (…) I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.

—Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain

The city was divided into four zones or campan. Each campan was divided on 20 districts or calpullis. Each calpulli was crossed by streets or tlaxilcalli. There were three main streets that crossed the city, each leading to one of the three causeways to the mainland; Bernal Díaz del Castillo reported that they were wide enough for ten horses. The calpullis were divided by channels used for transportation, with wood bridges that were removed at night for security.

After the conquest, Cortés leveled the ancient city and rebuilt it with a central area designated for Spanish use (the traza). The outer Indian section, named San Juan Tenochtitlan, continued to be governed by the indigenous population and mantianed the same subdivisions as before. The ruins of Tenochtitlan are located in the central part of Mexico City.

1450 Zuni Pueblo

The Zuni Indians and their ancestors have lived in the Zuni River valley and the surrounding region for more than 1,500 years.* Contemporary Zuni Indians are the direct descendants of the prehistoric Pueblo people who settled the region sometime prior to A.D. 400. Mirroring the developments that took place throughout the region occupied by prehistoric Pueblo Peoples, the first settlements in the area were built by farmers living in pithouses of various types. Later above-ground masonry structures (pueblos) were comprised of small, dispersed room blocks known as kivas.

Around 1000, the population in the Zuni area began to construct larger settlements oriented around Chacoan great houses with associated circular great kivas. In the mid-thirteenth century, the Zuni built much larger, plaza-oriented settlements in areas where more intensive agriculture was possible. More than 37 of these large villages were occupied between 1250 and 1540, incorporating an estimated 10,000 rooms.

By the end of the pre-Columbian era, the Zuni settlement comprised of a few, very large villages in a core area of habitation that contained the best agricultural land in the region. A similar development of settlement patterns occurred in the neighboring Acoma and Hopi areas. By 1550, the only occupied villages in the Western Pueblo region were the Zuni, Acoma, and Hopi pueblos.

Next week, my History of Urbanism series will look at the first Colombian era cities, including the oldest continuously inhabited European established settlement in Mexico and continental America.

1 thoughts on “A Brief History of Urbanism: Pre-Columbia Cities, Part 3”

Comments are closed.